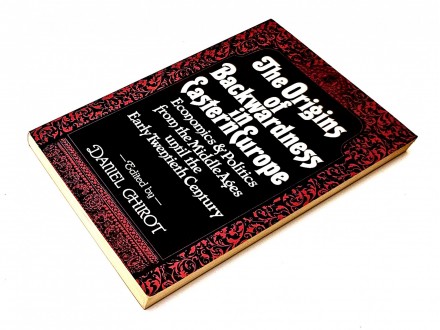

Ponuda "Economic Backwardness and Economic Growth" je arhivirana

Prijavom na sledeći link možete dobiti obaveštenje kada se predmet koji tražite pojavi

http://www.kupindo.com/Rss/pretraga.php?Pretraga=Economic Backwardness&CeleReci=0

Ukoliko još niste koristili RSS, pročitajte više o tome na Kupindo blogu:

http://blog.limundograd.com/2012/08/rss-ili-kako-da-uvek-znas-sta-je-novo-u-ponudi/

http://www.kupindo.com/Rss/pretraga.php?Pretraga=Economic Backwardness&CeleReci=0

Ukoliko još niste koristili RSS, pročitajte više o tome na Kupindo blogu:

http://blog.limundograd.com/2012/08/rss-ili-kako-da-uvek-znas-sta-je-novo-u-ponudi/